|

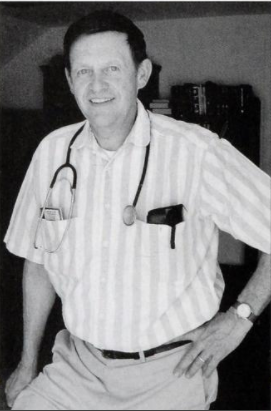

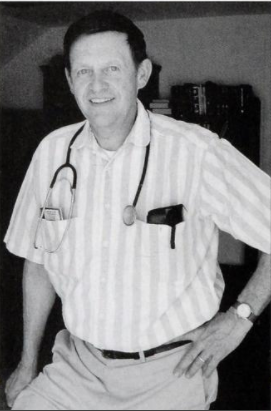

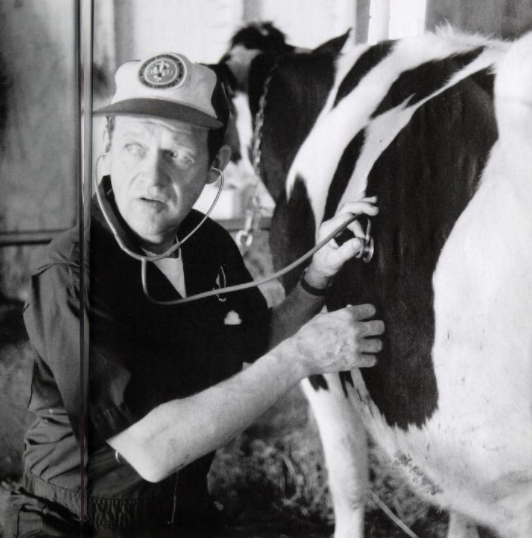

When Manchester veterinarian Robert Treat makes his rounds, he doesn't just travel through Bennington County and neighboring towns, he passes across entire worlds. Shoppers pursuing deals in Manchester's outlet stores cannot imagine the day's work that lies before the slender man driving by in the dusty brown Subaru.

Treat's own world stretches back to riding with his father, Edwin, who practiced veterinary medicine in Manchester for 50 years. He remembers impassable roads, livestock with brucellosis and TB, and logging camps where Edwin Treat traveled to minister to the draft horses. His world stretches forward to his son Rob, who has joined the family practice and accesses dairy herd information on his computer.

Treat, 58, and in his 32nd year of practice, gracefully navigates these different worlds as he performs herd checks with farmers whos' fathers knew his father and then returns to the office to vaccinate pets for people who have never been on the same side of the fence with a cow.

"When I was a boy," he says, "I knew I wanted a job where I wouldn't be inside four walls, but could be part of this environment. I also thought our nation's food source was a vitally important issue. I realized if I could contribute to disease-free animals, it would be helping people, and that would be a rewarding career, not just a way to earn a living."

"This is a compassionate man," says Manchester's Madeline Harwood, who has known all three generations of Treat veterinarians. "He is as concerned about the people who own the animal as the animal itself."

|

|

As Treat--known around the county as Dr. Bob--drives along the paved and dirt roads in Manchester and beyond, he sees a lot of things that aren't there anymore. "That used to be a farm," he says, pointing to an overgrown hillside. "And that used to be a farm," pointing in the other direction. "And that was a milking shed, and that was pasture." Everywhere his mind sees fathers and grandfathers, old farmhouses, barns with no electricity, and the broad, flat noses of cows.

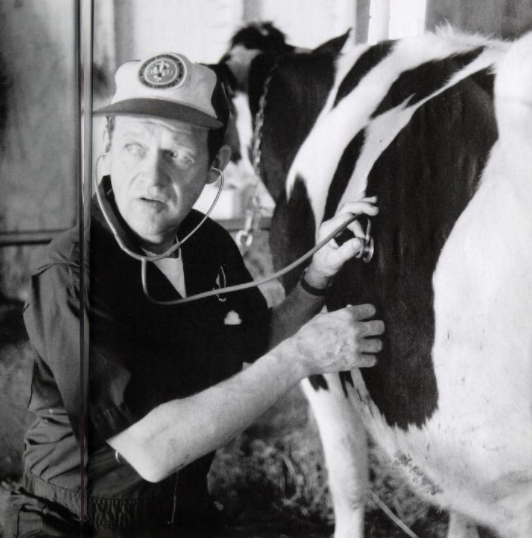

One dairy farm that still works is Bud Simonds', with 40 of his herd lined up side by side in a narrow barn in Manchester, munching feed Dr. Bob pulls on an arm-length plastic glove, scratches the tail of the nearest cow, murmurs something reassuring, and plunges in, reading with his finger-tips the uterus and ovaries, the cow's pregnancy or readiness for breeding.

Bud Simonds takes careful notes as they move down the line. The sound of a fan in a far window and manure hitting the concrete floor make it hard to hear the statistics, but Bud knows what he's listening for. His livelihood depends on these pregnancies.

Treat comments on Bud's dedication and the unspeakably long hours of a farmer's life. He methodically washes off his boots. He checks in with the office on his car radio to tell them he's headed to Fred (Shorty) and Sandra Stone's place in Pawlet. On the way he talks about Shorty's ingenuity and his risking an entirely new way of managing his herd. Part of the risk is immediately visible on the new, 274-fot-long open-air barn where the Stone's cows range freely. The set-up is different from Bud's but the concerns are similar, and once more Dr. Bob reads the heard.

After several examinations, Treat cleans up and drives towards Weston. When he checks in on the car radio, there is one question from the office: "Did you burn Queenie?" "Yes," he answers cryptically, "look on the bench." The night before, after untwisting a cow's uterus and delivering a calf, Dr. Treat made a late house call to a Manchester home where an elderly woman could no longer help her ailing dog. Dr. Bob took care of putting Queenie to sleep and, anticipating the woman's request, cremated the dog and left the remains at the office early in the morning.

|

|

|

"It wasn't until I was really in it that I saw the human-bond aspect of my work," he says. "I began to notice how much teenagers, especially girls, bonded with horses, and boys with their dogs...I noticed when we go to a senior citizens home that a pet cat will bring a lot of comfort to the older people. The bonding is emotional, and animals make a significant contribution to a person's enjoyment."

By 2 in the afternoon, without a food or bathroom break, Treat pulls up to Peter and Tia Rosengarten's newly built barn. Champion Angora goats and two alpacas bounce around a cleared hillside under the frenzied and practiced eye of a guard dog. No expense has been spared by the owners, who retired form business in Pennsylvania and clearly relish farming as a second career. "Normally I'd do several more calls," Dr. Bob says, settling into the Subaru after his visit, "but today I've just got one more, Jim Daley's foal with a swollen knee."

Dr. Treat's official hours end after the foal, but there will be emergencies the next day in the office, not far from the home he shares with his wife, Sally, and where they raised their five children. There will be a cat to be spayed, a Springer Spaniel with a face full of porcupine quills, and an obese dog needing surgery. Dr. Bob will confer with his son and their partner, Dr. Alan Lindsey, about a cow with a hardware problem (it swallowed barbed wire), a cow who stepped on her teat, and X-rays of a dog's elbow.

|

|

Does he think about Manchester before outlet stores, or a time when horses weren't pets, but work animals? "You can't be afraid of change," he says. "But the future of this practice is tired up with what the state does. What our practice will look like in 10 years is a question of farmland versus development."

Meanwhile, an elderly woman waits, cradling a dachshund in an old crocheted blanket, and there's a dog in the kennel that hasn't touched it's food in four days after surgery. Treat checks for toasted English muffins in his mother's kitchen in the house next door to the clinic. He brings some back to the fasting dog who, it turns out, was only waiting for some decent people food. Dr. Bob cares for the animals, and cares about their owners and quietly contributes to his corner of the world.

|

Article written by Alisan Freeland for Vermont Life - published Spring 1996

Photographs by Owen Stayner of Burlington, VT

|